Search this site ...

Resistance art

Resistance Art - In South Africa, the years 1968-1971 saw a window for relatively free expression before the Government clamped down on cultural groups linked to the Black Consciousness movement.

This opportunity in time that was reflected in an exhibition shown at the Durban Art Gallery called 'Art, South Africa Today'. Pre-1970, most political art was socio-reflective, concerning the human condition, primarily suffering. But this exhibition which had 3 key jurors, namely Neville Dubow, Walter Batiss and Esme Borman, seemed to support works of art that were more confrontational than usual and referred to the socio-political circumstances that were prevailing in the country at the time. Nearly all the artists who were a part of this new wave were in their 20's, many of whom are leading lights in the art world today. The general reception of this show was favourable but the formal institutions balked, finding the nature of the content too challenging; they felt art and politics should not mix.

It would take another decade for overt political protest in art to assert itself.

During this period a great number of small workshops and independent art centres bounced up as a rebuff to the closure of more widely known centres like Polly Street.

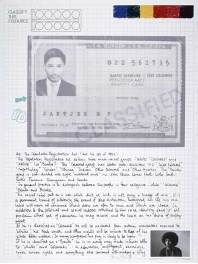

11 prints, mixed media

11 prints, mixed mediaCertain individuals like Gavin Jantjes had managed to slip into mainstream art courses by being re-classified by colour. (Jantjes was an artist of 'coloured' heritage). With all the advantages of formal tuition and use of materials at Michaelis School of Art in Cape Town, he developed into one of the country's foremost printmakers, technically highly skilled and aesthetically fuelled by great passion against the inequalities of living in SA.

The prints seen above are one of the most hard-hitting critical commentaries and reflections on the apartheid era, exploring racial classification, conflict and abuse. Containing 11 images plus the cover Jantjes uses the irony of colour in 'A South African Colouring Book' to emphasize how the State was obsessed by categorizing everything by colour. Since he was living in Germany in exile when he created this series, he used Ernest Cole's book of apartheid photography titled 'House of Bondage' as reference. Jantjes settled in Britain in 1982 where he consulted for the UN on refugees, serving on the advisory board of prestigious public galleries like Tate Liverpool, curating exhibitions and acting on the Arts Council of Great Britain. He currently lives in Oslo.

The State initially saw the Black Consciousness movement as a triumph of ethnicity which they thought would illustrate the success of separate development. However as the movement grew in threatening momentum and influence, they reacted violently, clamping down and enforcing censorship, stopping the flow of discourse that existed. Cultural venues were controlled and investigated.

Despite this policy a vibrant and independent non-racial culture was forged by artists and activists working in alternative communal organizations and centers like the Bill Ainslie Studios (then became the Johannesburg Art Foundation), Mofolo in Soweto (carry on from Polly St Studios), Katlehong in Germiston, Black Art Studios in Durban, the Community Arts workshops in Durban and Community Arts Project and Nyanga in Cape Town, Alexandra Art centre, Funda in Soweto and Fuba (Federated Union of Black Artists), the first black art gallery in 1977 in Market Theatre precinct, Johannesburg.

Young artists such as Willie Bester in Cape Town and Sam Nhlengethwa in Johannesburg used the Art Centres to formulate their beginnings in a turbulent era.

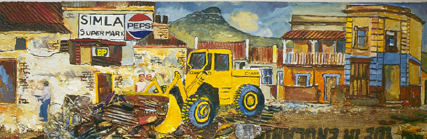

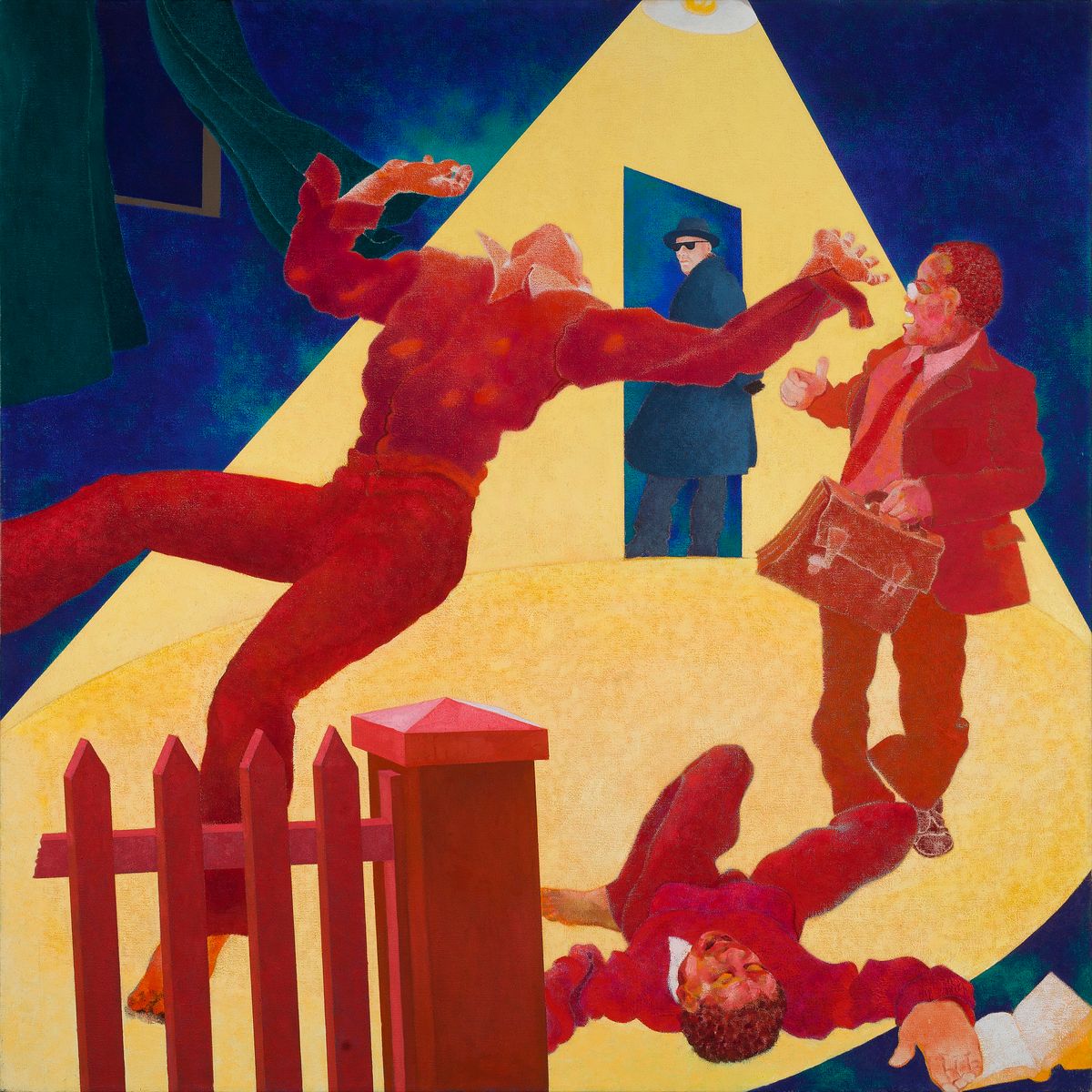

Willie Bester,'Forced Removal'

Willie Bester,'Forced Removal'The prevailing mood was not to be crushed and in 1976, the Soweto uprisings transformed SA into a living hell for those who were forced to live on the dark side of apartheid.

By the 1980's art had lost all trace of innocence and any progressive art piece that was worth its salt was tackling issues head on without visual constraint. Nothing was spared in stark, brutal images that pushed the same boundaries that those children did in Soweto in 1976; it seemed to have touched the nerve of the nation and fear disappeared. Almost every artist produced overtly political work, taking up brush and paint as weapons against the oppressed.

A 'State of Art' conference was held at Michaelis Art school in Cape Town and artists like Gavin Younge, Marlene Dumas and Paul Stopforth visually recorded on the 'Resistance Register', a series of photographic screen prints by Younge in 1975-6, pledged themselves to 'committed art', making a conscious decision to effect change by not taking part in State sponsored exhibitions until change occurred. Many protest artists began to develop very specific and unique styles: Robert Hodgins, Norman Catherine, Helen Sibidi, William Kentridge, Penny Siopis, Jane Alexander, Willie Bester and Sue Williamson.

A key conference was held in Gaberone, Botswana in 1982 called 'Art Towards Social Development and Change in South Africa' with an exhibition of politically directed work and addresses and papers delivered by currently involved artists. Many exiles were in attendance.

Artists

Helen Mmapula Mmakgoba Sibidi, b 1943. Sebidi is an extraordinary woman whose extra ordinary art will be a legacy to the condition of black women living and working through a very turbulent era in South Africa's history.

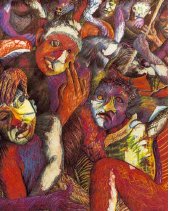

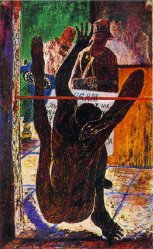

'Mother Africa'

'Mother Africa'It would be easy to loose one's critical attention to her work because her art is so tied up in the socio- political aspect of the times and she dealt intensely and dramatically with women's issues and the suffering of apartheid in the townships.

Tense, crowded collages seek to portray the struggle, her figures battle upwards to the surface out of the drowning mass. Rendered in vivid colour using crayon and broad, jagged brush strokes it seems to emphasize the tension and angry energy of the artwork.

But the enduring quality of her art is her reverence for her traditional Tswana cultural practices and philosophies which are expressed in her uniquely modernist work. Her grandmother was a traditional floor and wall painter and Sebidi reflects this cultural heritage in the use of reoccurring motifs and the symbolic employ of animals in her work.

She herself was driven by an innate desire to create from a very early age, at the earliest opportunity involving herself not only in her own art education at John Mohl's 'White Studio' and the Johannesburg Art Foundation (where one especially significant workshop shifting her work into a new idiom, part figurative, part abstract) but she also helped others by teaching at Katlehong and Alexander Art Centres and being involved with community art projects such as Funda and Thupelo Workshops.

In the late 1980's she was awarded a Fullbright Scholarship and in 1989 she achieved acclaim by being awarded the Standard Bank Young Artist of the Year. She has been included in the Taxi Series of books published by David Krut which in itself is massively significant as it has shifted emphasis away from the strongly male contingent of black South African contemporary artists.

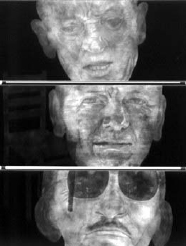

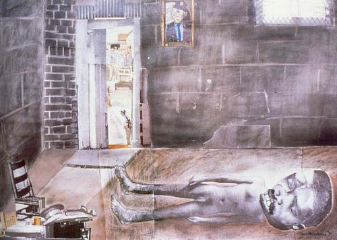

Paul Stopforth's work introduced for the first time the real faces of the perpetrators of violence under the auspices of apartheid. He produced works that were a testimony to those forces like a series of plaster-of-paris and wax figures which were life-size images of men in tortured poses of suffering. 'Elegy' is a series of 20 works in graphite and acrylic that were a homage to Steve Biko.

Stopforth's work introduced for the first time the real faces of the perpetrators of violence under the auspices of apartheid. He produced works that were a testimony to those forces like a series of plaster-of-paris and wax figures which were life-size images of men in tortured poses of suffering.

'Elegy' is a series of 20 works in graphite and acrylic that were a homage to Steve Biko.

Stopforth chose to leave South Africa in the late 80's and has settled in the USA where he lectures at Harvard University.

He continues to produce beautifully crafted work which has become less political or provocative but still fully engaged with the world.

Jane Alexander, b 1959. Alexander's work is as much about the art as it is about the viewer.

Stark, brutal and deliberately confrontational it allows no escape for the viewer who is drawn into the world she has chosen to portray with her iconic sculptures and photo montages and who has no choice but to examine the platform upon which he/she, as the onlooker, stands.

Her work from this era is deliberately made in this manner so that she does not need to explain herself. It is reflective of the society under apartheid, its members in their insecurity becoming both aggressors and victims. The sculptures are made with reinforced builders, plaster, fibreglass, paint, found objects, occasionally bone and she uses props like chairs, benches, ammunition / explosive boxes, fences, earth, gloves, machetes and sickles.

In 1982 while still at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg she produced 'Untitled', two skeletal figures hanging from a frame; carcasses with animal skulls and human bodies. She discovered that violence enthrals viewers and a sculpture like 'Dog' depicting an animal dragging human thighs had a mesmorizing effect on the public.

detail

detailButcher Boys is the most visited artwork in the Iziko South African National Gallery Collection in Cape Town. Three figures reveal aspects of violence and yet are more passive than her previous work and in this manner this restraint makes them hugely more sinister and they become everyone's abhorrence.

I think this why the piece endures so well; it has moved beyond the era and is eternally connectable. All violence and cruelty is contained and transposed in these grey underworld world figures.

Alexander has continued to produce arresting work. The 'Bom Boys' was produced in 1998 and this tableau was shown on Africa Remix in Düsseldorf, Paris, London, Tokyo, Stockholm and Johannesburg in 2004.

For insight into her more recent work have a look at this web site.

By the mid 1980's South Africa had erupted into conflict with the imposition of a State of Emergency. With it came oppressive conduct from authorities resulting in an upsurge of clashes, riots, strikes which were mostly brutally dealt with.

Reactive artists like Manfred Zylla, Kevin Brand, Andre Van Zikjl, Bongiwe Dhlomo and Gary Van Wyk produced images that pulled no punches and portrayed the reality of the situation.

Manfred Zylla, b 1939- Zylla used his art as a tool to demonstrate the inequalities and the atrocities experienced by people living under the effects of the imposed State of Emergency.

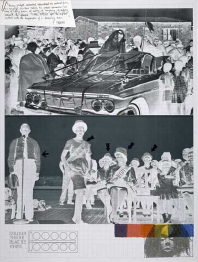

Working with mixed media and pencil on paper he recorded particular events such as the Trojan Horse' episode in 'Death Trap' and the 'Instigator'.

He initiated a venture that encouraged the community to involve themselves in expressing their feelings regarding the tyranny of apartheid by inviting them to add to his finished pieces which he had been working on at the Community Arts Centre in Cape Town. Over 200 people came and joined in; it was a liberating and cathartic experience for all despite Zylla having to sacrifice his pieces.

This artwork piece by Ramphomane refers to an incident that created personal trauma for himself and his relatives when police made a threatening visitation to his house in Soweto demanding rent during the rent boycotts.

Sue Williamson, b 1941- completed a 2 yr fine art diploma at Rorkes Drift in 1977-8 and during this period produced her first series of prints, etchings called The Modderdam postcards.

In 1981 in response to bearing witness to the bulldozing of District Six she created an installation piece called 'The Last Supper' which featured piles of debris surrounded by 6 chairs covered in white cloth, symbols of mourning for all they had lost. At the same time music was played to accompany the visual image; capturing all that the district encapsulated; mosques, music, calls of the inhabitants and overriding it, the sound of bulldozers.

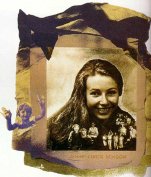

Later in 1982, she created 'A Few South Africans', etched and silkscreened portraits honouring women who were heroines of the struggle like Winnie Mandela, Albertina Sisulu, Charlotte Maxeke and Mamphela Ramphela among others.

This was followed by 'Portrait of Jenny Schoon' who died in a parcel bomb along with her small daughter and then in 1990 'For Thirty Years next to his Heart, featuring a pass book, that symbol of black people's lack of freedom and in 1993 she created Momentoes of District Six along the same theme as 'The Last supper'.

Socially aware and fearless in presenting in her art what she feels needs to be exposed or brought into the mainstream's consciousness, she continues to actively engage the viewer with the subject and the story she wants to portray. She makes visible the unseen and the hidden.

Norman Catherine b 1949

His first solo exhibition was with Goodman Gallery in 1970 and incorporated all sorts of material for which his innovation of usage is legendary.

He is best known for his sculptures but is technically highly proficient in airbrush and dry point etchings. Common to all his methods is a searing wit and a dark cynicism that was fuelled by South Africa's apartheid government and particularly the existence of the State of Emergency.

Early works feature titles like Suicide, House Arrest and Intensive Care and are raw expressions of his abhorrence to the political intolerance and suppression. In 'Dog of War' and 'Carnivores' he comments it is 'the animal in man that I am portraying his carnivorous aspects, his territorial instincts.'

The second half of the 1980's brought about a change; the cultural activism generated by the Botswana conference had been absorbed and whites in South Africa felt they too had a stake now in the great effort for freedom.

The Market Theatre Precinct and Rocky St became thriving centers for multi-racial gatherings, performances and social groups that took risks in expression and demonstration. A truly African identity was beginning to be formulated by all artists, a unifying force.

An exhibition that took place in 1985 called Tributaries and curated by Ricky Burnett was important not only for having the first, almost equal participating numbers of white and black artists but also placed unique craft and progressive indigenous sculpture alongside the 'fine art'. The homelands of Venda, Kwa Ndebele and Gazankulu, in their isolation were producing a whole new breed of sculptors who mixed religious zeal together with traditional cultural influences like dream references and a great deal of passion and political fervor.

Artists such as Johannes Segogela, Tito Zungu, Nelson Mukhuba, Dr Phutuma Seoka and Johannes Maswanganyi were exposed along with Jackson Hlungwani and Noria Mabasa; a whole new generation of African sculptors.

Other significant artists of this whole period of resistance art from 1970 to 1990 amongst others are: Dumisani Abraham Mabaso, David Moteane, Paul Elmsley, Pippa Skotnes, Hardy Botha, Sfiso-Ka-mkame, Chabani Manganye, Sandra Kriel, Clive van den Burg and Andries Botha.

Also Vuyile Cameron Voyiya, Kendall Geers and Sam Nhlengethwa...see below.

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.