Search this site ...

African beads and beading

In Africa, beads have transformed and elevated the ordinary while conveying status, access and prestige to both the wearer and the crafter.

Throughout the centuries, African artists have created intimate, beautiful works of art that are integral to social and spiritual life. Many of these pieces are encrusted, woven or threaded with beads made from a vast array of materials.

Using these small, decorative, spherical objects, artists have communicated messages about identity, politics, religion and social culture.

History of beads in Africa

Determining the source of beads found in Africa is a hugely extensive research field and there are many publications one can read through, not all them being irrefutably proven given the nature of the task at hand. But one thing is for sure, beads unearthed in Africa can give us a feel for the movement of trade and people across continents and across seas.

Beads were first made thousands of years ago from organic materials such as bones, shells and seeds, horns, teeth, quills and stone. Beads and organic objects were, and still are in some tribal areas, assembled and strung together on muscle fibre, leather cord, animal hair, cotton or gut.

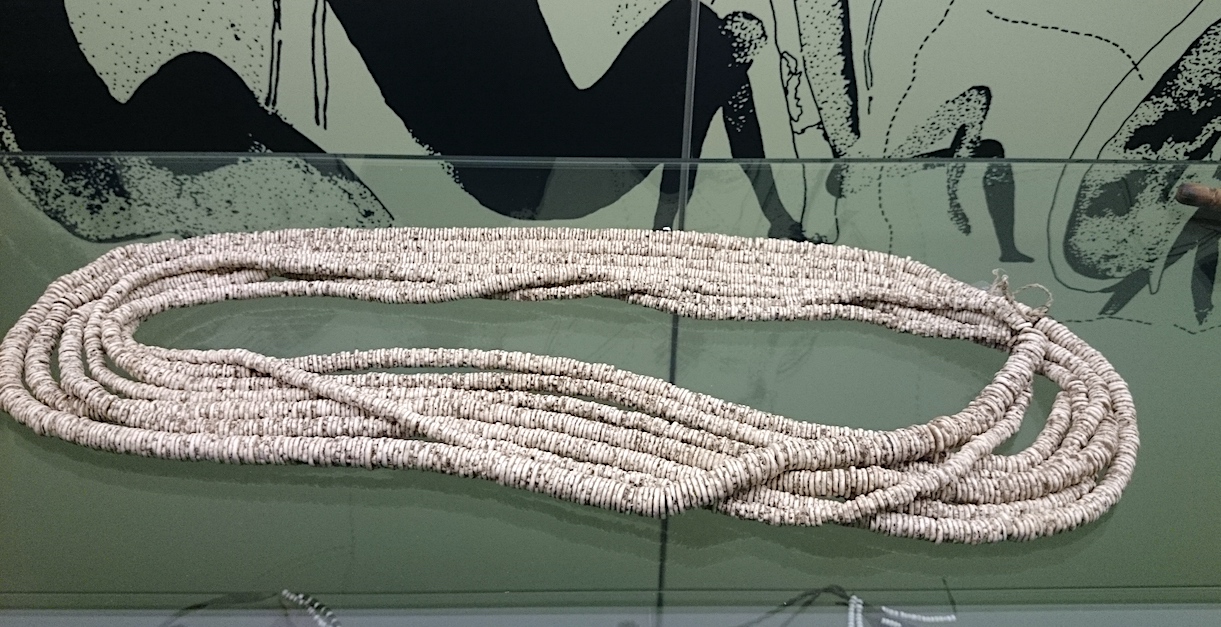

Ostrich eggshell necklaces were some of the earliest forms of jewelry and while most of the ancient beads such as these seen below from an archaeological dig, do not survive today, they are not dissimilar to the various beaded items of 19th C Namibian and San tribes of Southern Africa.

Eggshell jewelry crucially illustrates how and when humans begun to modify natural shapes into a variety of forms for both practical and aesthetic purposes.

The earliest tangible evidence of land links and connections between Southern Zambesia, the East coast of Africa and the Indian Ocean world comes primarily from the discovery of glass beads belonging to the Zhizo period (AD 600-900) at sites in Chibuene, southern Mozambique, Makuru, central Zimbabwe and Schroda in the Limpopo valley. Some Zhizo beads were also found in north eastern Botswana on the edge of the Kalahari Desert.

These soda-lime, silica glass beads were not only spherical but were also tubular, cylindrical, oblate or barrel shaped and most likely came from Mesopotamia, the Euphrates and Tigris River systems of Western Asia. Later they appeared from India and South and Central Asia.

Some of the first, imported powder-glass beads appeared at excavations in Mapungubwe in the southern region of South Africa, dating from 970 to 1000AD and Great Zimbabwe has recorded excavated beads which date from the 11th C and are macroscopically indistinguishable from Mapungubwe types.

After this Khami beads were used and these were followed by Portuguese-period glass beads which lasted until colonisation in the 19th C. For further details from this source, read here

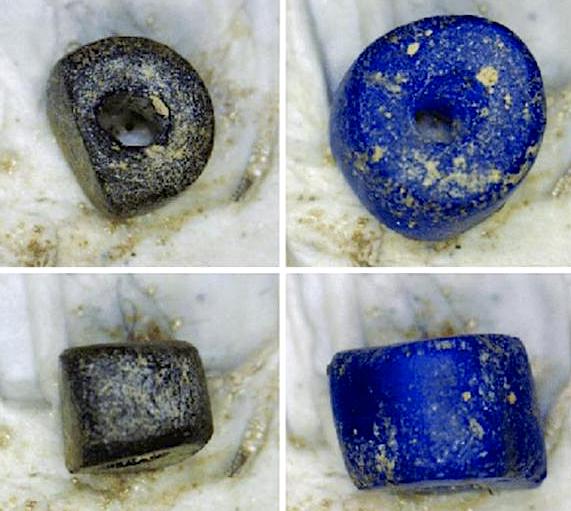

Ancient Nila beads,Mali

Ancient Nila beads,MaliNila beads have been excavated in Mali, particularly in the Djenne region which is one of the oldest trading routes in Africa, a vital crossroads for for the gold and salt trade.

These blue glass beads were made elsewhere (indeterminate) and brought in on one of the ancient caravan routes during the 11th to 15th Century CE.

Very recently, the analysis of glass beads found at a Nigerian site at Igbo Olokun has revealed that a unique, sub-Saharan glass production industry existed prior to the arrival of foreign traders in the early 16th C. Archaeological investigations since 2010 have revealed the existence of the first known W African primary glass-making workshop dating to early 2nd millennium CE which supplied glass beads for the regional trade network.

Researchers are confident beyond doubt that the groups of glass found represent a glass produced in early Ile-Ife using local recipes, raw materials and technology.

Evidence of glass bead production is found in these notable areas of today such as Ghana, the Krobo and Ethiopia. Ground particles are compacted prior to firing... a painstakingly slow process known as wet-core production.

By the mid 16th Century, a wide variety of glass beads were being made in Europe.

Africans traded ivory, gold and slaves for these beads and they were introduced all over the continent as currency. Africa's golden trade Era stretches from 1700 to 1920 reflecting the highest levels of trade and economy.

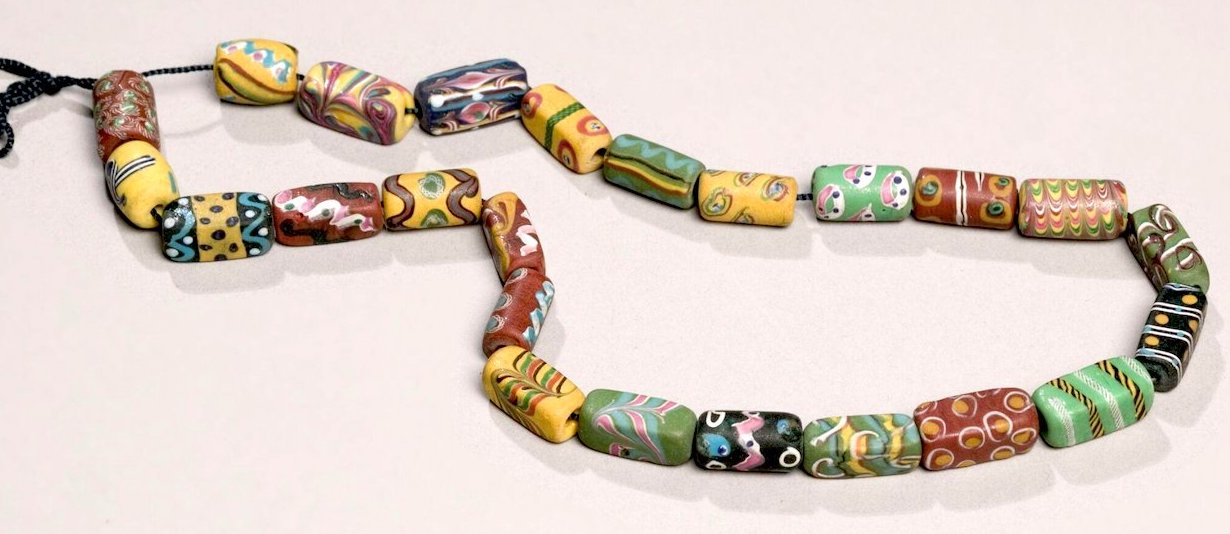

These glass beads are of the kind known as trade, aggry or slave beads. Usually associated with West Africa, they were created in Europe dating back to the 15th C when Portuguese trading ships arrived on the coast of W Africa. The beads provided a cheap and efficient means of exploiting African resources like gold, slaves, ivory and palm oil.

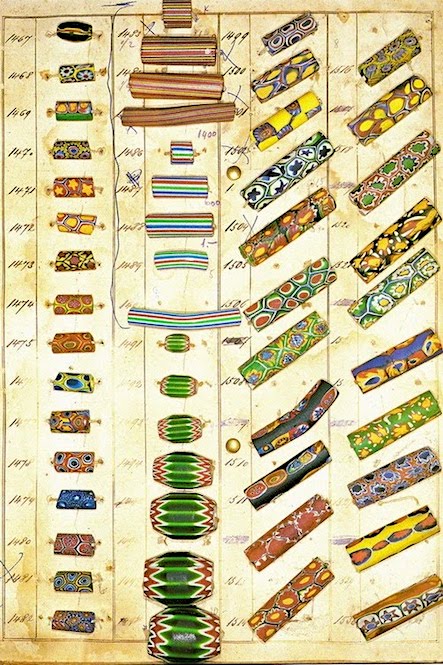

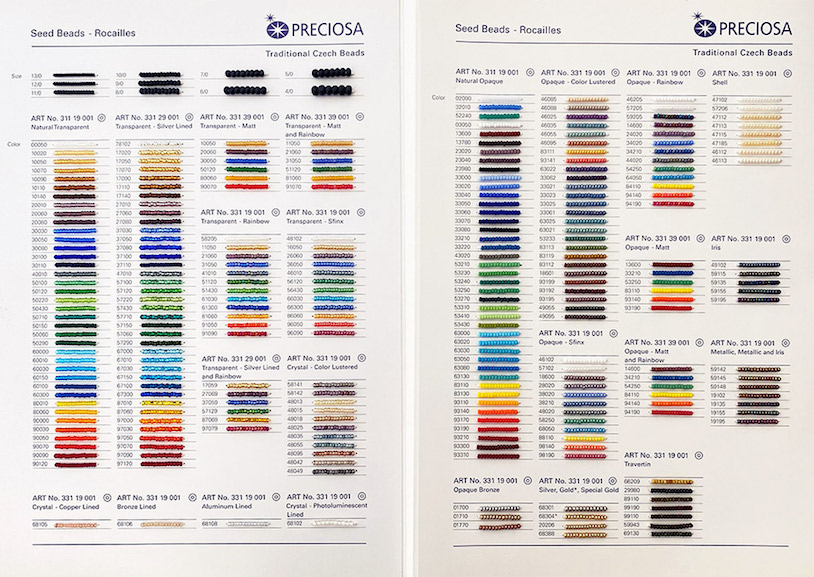

The number of people involved in this trade from so many different countries makes it very hard to establish the provenance of the found beads or strands, but dealer catalogue cards produced by European bead trading companies in the mid 19th C to early 20th C, can help date and locate the source of the beads.

Trade bead catalogue card

Trade bead catalogue cardIn the 16th Century, small glass seed beads became highly popular in specific regions within Africa like Central, Eastern and Southern countries whose artisans applied their incredible skill and artistry to fashioning all sorts of garments, jewelry, furniture and artefacts.

East Africa and Southern Africa still make great and varied use of them today for personal attire, tourism craft, decorative jewelry and homewares.

Use of beadwork in African societies

For centuries African beadwork has played an important role in defining social status and heirarchy. Beads have been used in their 1000's to create artistic and impactful designs on all nature of things. Many of these beading creations have come to identify the social and ethnic groups who make them, as well as the life stages of the individuals.

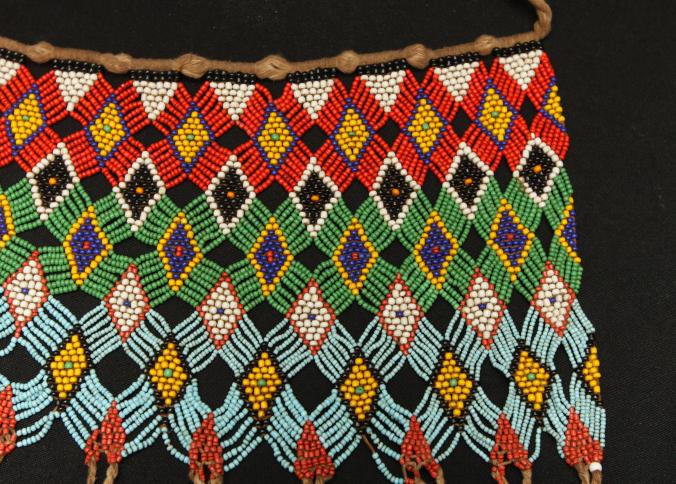

African beaded items have been used to celebrate and symbolize womanhood, sexuality, femininity, fertility, healing, spirituality, menstruation, wealth, seduction and marriage. They are also insignias of power and status and are emblems of the political, social and religious complexity that can exists within some African societies. Such as this magnificently preserved piece featured below....

Hat (Kalyeem), early 1900s, DRC-Kuba raffia, glassbeads, cowrieshells, cloth Cleveland Museum of Art

Hat (Kalyeem), early 1900s, DRC-Kuba raffia, glassbeads, cowrieshells, cloth Cleveland Museum of ArtWithin the different societies, particular rules applied to various individuals within that community. An example of this is by status, is the Kuba tribe whereby only the King and his immediate family can wear a belt holding multiple small pendants covered with beads and cowries. This one below has 23 pendants, the large shells bearing testament to the king's control over long distance trade routes.

The beaded headdress (Adenla) featured below on the left was commissioned in the mid 19th Century by a Yoruba king, Oba Edun of Okuku to celebrate his reign. The artist is unknown but the piece is made of beads, cloth and wood and fully exhibits his talent and his creative response to working with beads to embellish the conical crown worn by the king on ritual occasions.

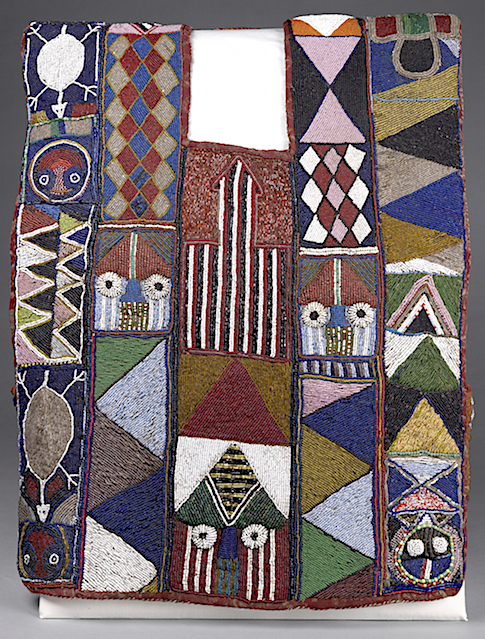

As trade increased with colonization, greater access resulted in a flourish of beaded regalia in the artistic centre of Elon-Alaye, Nigeria. This magnificent, densely beaded tunic was created in this regional centre for an obviously powerful individual.

In the Grassfields of Western Cameroon powerful, competing rulers became major patrons of the arts and commissioned many examples of beadwork to express their power and prestige.

This throne is from fon Njouteu's treasury and depicts a king and his consort standing at the back of a circular seat supported by a leopard. Up to 8 different types of bead are used in this incredibly complex and beautiful piece of noble furniture. To construct it an artisan covered the wooden sculpture with raffia cloth and then artfully applied thousands of glass beads onto the surface.

Detail of necklace using Venetian glass beads including chevrons

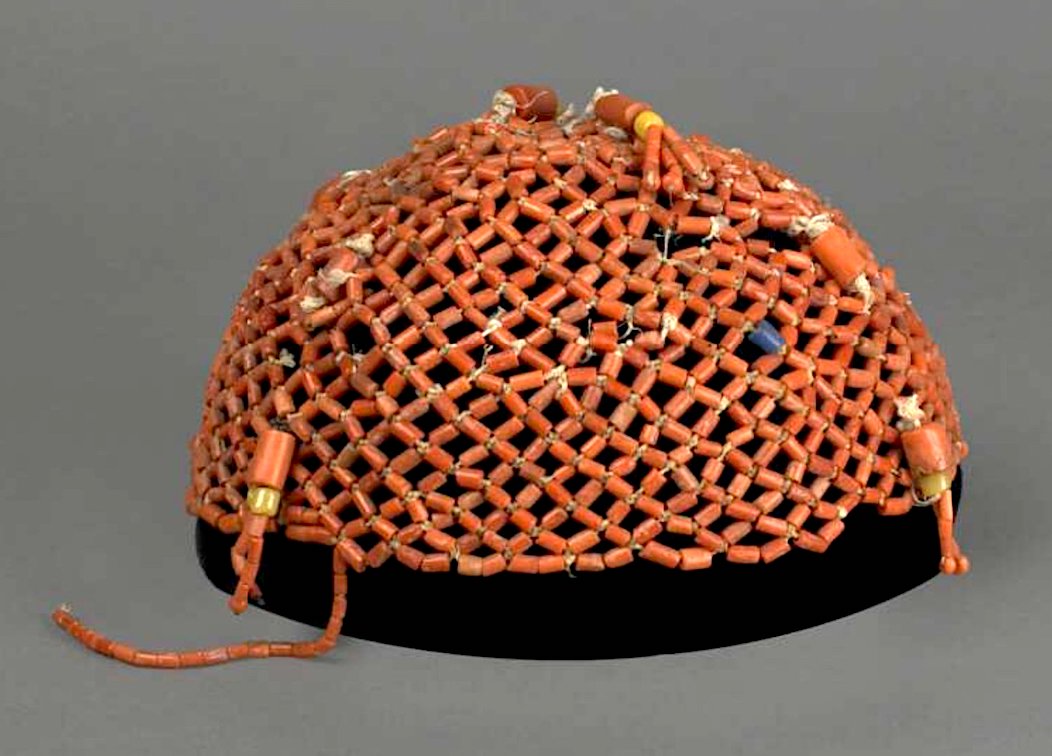

Detail of necklace using Venetian glass beads including chevronsCoral beads from the Mediterranean Sea have a special place in African bead history. Towards the end of the 15th C coral beads constituted one of the principal commodities being traded with the Kingdom of Benin in present-day Nigeria. All coral beads were the property of the king or oba who had the sole right to distribute them where he saw fit.

The oba was permitted to wear a complete costume of coral beads; crown, collar, robe... even shoes. Decorating and enhancing the body, they also portrayed a symbol of power and wealth.

Cache-sexes are small aprons used to cover genitalia and they provide some of the most intricate patterns and beautifully worked examples of bead art.

Often asymmetrical in their design detail, they are usually richly colored and patterned with geometrics and are often adorned and fringed with cowrie shells hung by natural fibre thread. They are tied round the hips with leather or string.

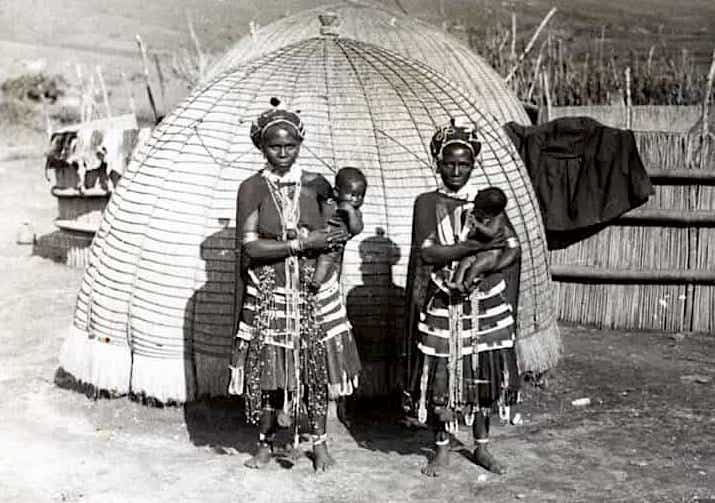

Ndebele and Zulu tribes from Southern Africa as well as Maasai and Turkana tribes from East Africa all wear tribal beaded garments which include cache-sexes, waist beads, corsets, aprons, capes, headbands and headdresses, bags and various forms of jewelry (necklaces, bracelets, anklets, earrings, rings, armbands, neckbands... you name it, they wear it, often all at once!)

Main garments can also be embellished with beads; skirts, loin cloths, tops and dresses.

On a more serious note, some of this attire is steeped in meaning and history and has great societal function and value. The practice of wearing beaded garments helps to regulate behavior between genders. For example, once married, a young woman is entitled to wear a beaded blanket cape called a 'Ngurara' probably handed down from a grandmother... and an 'Isiphephetu' is a beaded apron worn by adolescent girls symbolizing her journey from childhood to adulthood.

One particularly interesting accessory is a beaded belt known as an 'umutsha'. Both sexes can wear one although they are traditionally made by women who create belts for their whole family. The main body of the belt is leather or cloth but it covered with beads in all sorts of patterns, colours and designs.

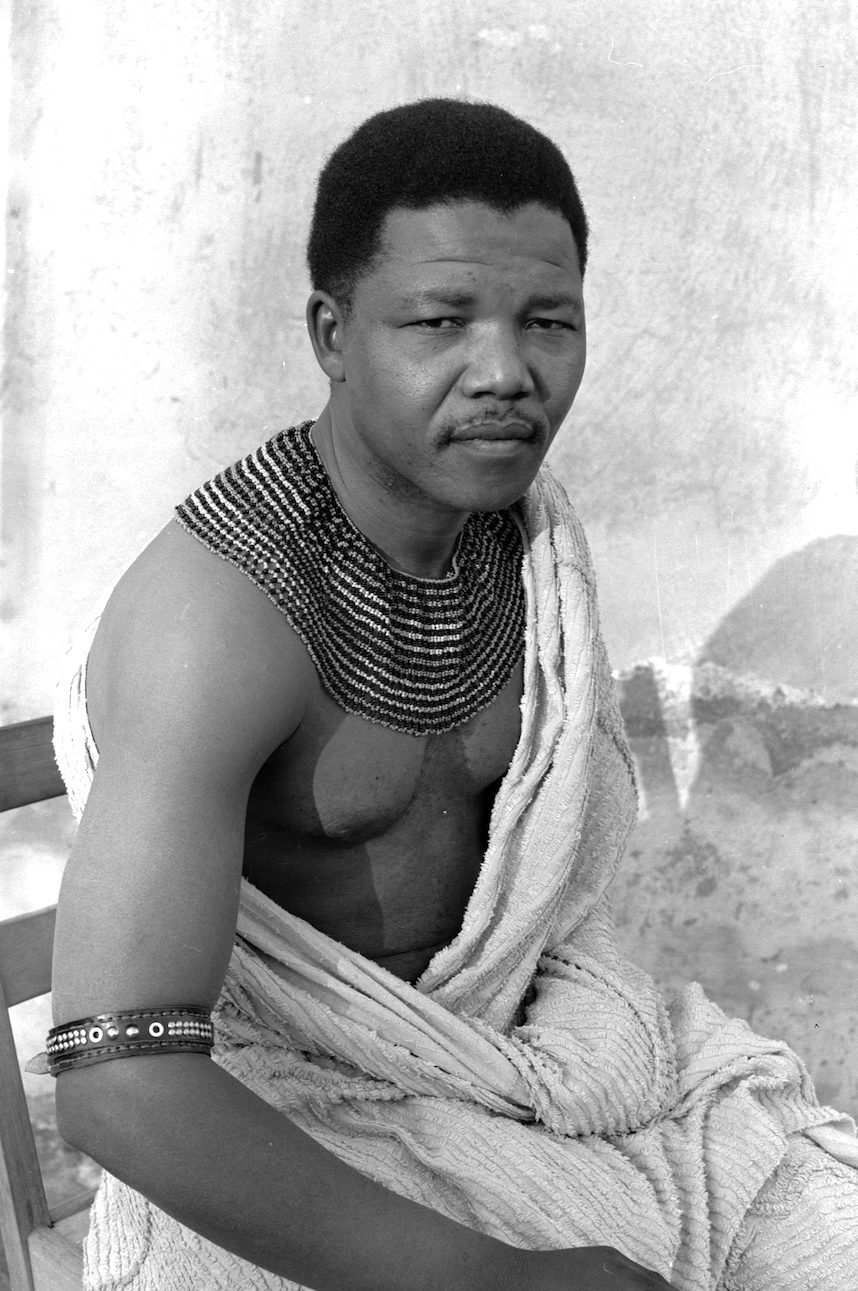

Xhosa males and females from South Africa wore beaded collars in the early to mid 20th C for special occasions and ceremonies. Thousands of small glass seed beads were painstakingly threaded and woven together to form a multi-layered beaded semicircular necklace.

For the Ndebele, beadwork and the expression of cultural identity made powerful political statements during the periods of colonialism and apartheid as authorities were against expressing 'an independent past'.

The most famous South African of all wears a beaded collar for his trial in 1962 which was taken as an affront to a European suit and expressed part of his wish to delegitimize the authority of a European court in Africa. The court was stunned into silence.

With the introduction and exposure of European style art for art's sake, African artist began to experiment with painting in different media. Art moved from a level of craft to a practice that would expand the horizons of some artists.

Modern bead art

Two African artists born mid-20th Century began to work with beads to create revolutionary beaded canvases that still hold their place today in the contemporary world. They are...

- Chief Jimoh Buraimoh b 1943, Nigeria

- Sanaa Gateja b 1950, Uganda

Chief Jimoh Buraimoh

Jimoh Buraimoh is a contemporary Nigerian artist, one of the original graduates of the 1960's experimental workshops known as the Oshogbo School of Art where he learnt printmaking and mosaics before moving on to beaded paintings.

These works are reminiscent of the fully beaded Yoruba cloaks, crowns and stools. Buraimoh expressed a fascination with these crowns, with their "shimmering colors, designs and patterns" and above all their grandeur.

Beads are string on to cotton threads and then glued to the surface of aboard, creating raised surfaces and an illusion of depth when placed compactly sidebar side.

Buraimoh's artwork is in collections all over the world both private and public and often come up on auction being one of Africa's pioneering contemporary artists. He has achieved many awards of excellence and is also a dedicated teacher, involving himself with many projects in all sorts of countries, places and institutions like October Gallery in London and Atlanta's airport in the USA.

Sanaa Gateja

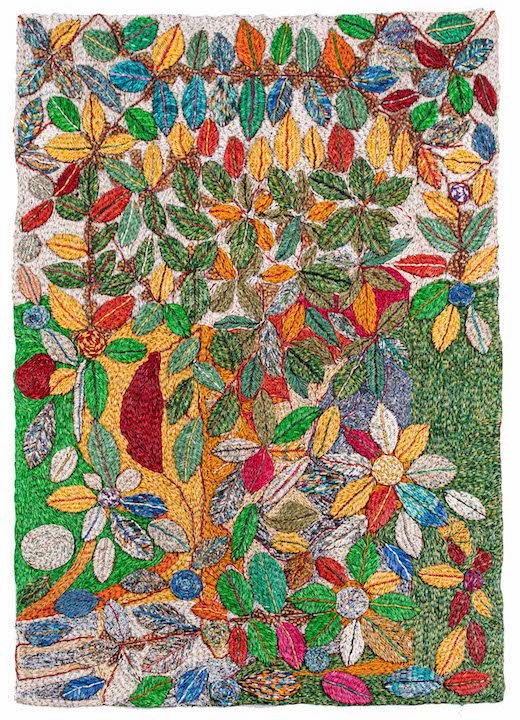

Sanaa Gateja is a multidisciplinary artist, working in recycled man-made waste.

His artistic practice of fashioning wastepaper into paper beads assembled into figurative or abstract paintings, has earned him the name 'Bead King' in his home country of Uganda. He studied jewelry design at Goldsmiths and interior design in Italy and has exhibited his assemblages extensively across Africa and also internationally.

In more recent times his pieces are large, experimental, abstracts that straddle tapestry, installation and sculpture. Featured here are his beaded tapestries....

His practice at his Kwetu studio in Kampala involves many members of his community and provides employment in helping collect waste, make beads and assemble large pieces, costumes and accessories. He also trains young artists and craftspersons to develop new and unique styles using his explorations as inspiration.

Featured below is a very recent piece of Sanaa Gateja's which was a collaboration between the artist and the Scottish artist Deveron Arts, together with the curator of African Collections at the National Museums Scotland, Sarah Worden.

'shoulder shawl' detail

'shoulder shawl' detailIt is described by Gateja as a shawl and incorporates thousands of multicolored beads hanging from the traditionally styled, beaded, collar yoke. Each bead has been hand rolled from waste material into tubular beads that are then varnished to strengthen and protect them.

The original matter was school catalogues and the letters and writing can still be discerned in the finished beads.

Colourful and intriguing, this bead-work shawl by the contemporary Ugandan artist, Sanaa Gateja, transforms waste paper into a statement piece of art and fashion.

For a further look into contemporary African bead art and artists go to this page

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.