Search this site ...

African Modernists

In the 1940's, through the works of the African modernists, contemporary art on the continent was seen mostly as a sociological commentary on modern Africa and hardly considered as a serious, creative expression of its people. African art was primarily associated to 'primitivism' and its influence on cubism and other forms of post impressionistic art.

In 1967, the Harmon Foundation, USA published a book called 'Africa's Contemporary Art and Artists'; a descriptive compilation of artists living in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Foundation had been collating visual information and collecting work by African artists since the 1920's. This was the first time African art had been presented as a modern art form and not something tribal.

The African modernists were finally recognized.

Ben Enwonwu, River Niger landscape, 1965

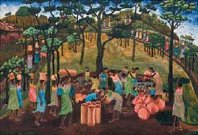

Ben Enwonwu, River Niger landscape, 1965 San Ntiro, Market day

San Ntiro, Market dayEmerging African modernists invented their own interpretation of modernist aesthetics with specific forms of visual languages that may or may not have paid allegiance to their culture; they were not bound by 'authenticity' or primitivism and since some of them had studied abroad they embraced what modern movements and methods they responded to without compromising their individuality.

Schools like Ecole de Dakar, Senegal aligned itself with Negritude and made formative contributions to exposing African modernists. They believed that culture was the foundation stone to rebuilding post independence nations and that artists contributed in a most valuable way to giving expression to the new consciousness of a nation.

In 1969 an exhibition was held in London that was quite visionary, attempting to show the works of many key contemporary figures who were developing, or had already developed, non-traditional art forms. Many of these exhibiting African modernists are fully established, recognised artists today like Malangatana, Twins Seven Seven and Onobrakpeya.

I believe there were 3 pioneers of African modernism:

- Ernest Mancoba, 1904-2002, South Africa

- Ben Enwonwu, 1917-1994, Nigeria

- Ibrahim El Salahi, b 1930, Sudan

Esteemed modernist artists from the continent include:

- Jimo Bola Akolo, b 1934-2023, Nigeria

Ernest Mancoba

He is slowly being recognized as one of the great artists of the 20th Century and acknowledged as a forerunner to the abstract expressionistic movement.

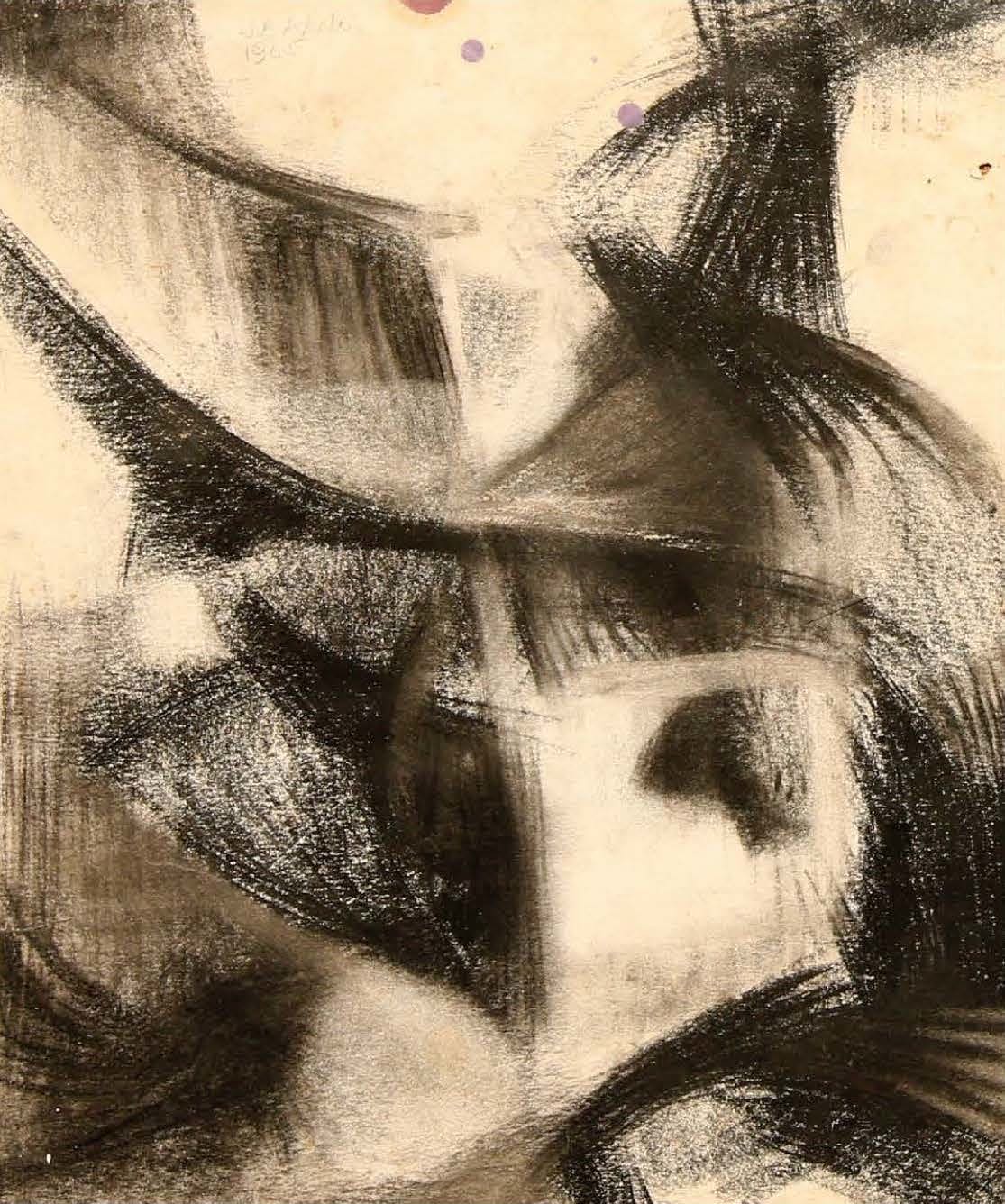

Ernest Mancoba, 'Untitled'

Ernest Mancoba, 'Untitled'But his real contribution is his assistance in the construction and definition of African modernity by which the language rules of contemporary African art were established. He was challenged to become a modern painter and sculptor rather than a traditional maker of forms. He believed there is no distinction between figurative and abstract art for African modernists.

In his homeland of South Africa he broke barriers very early on in his artistic career by sculpting the first black Madonna in 1929. This sculpture represented an attempt to get back to his cultural roots having being brought up in a Christian missionary environment.

African Madonna

African MadonnaWhile working in Cape Town in District Six he came into contact with artists such as Irma Stern and Lippy Lipschitz, the latter who introduced him to a book called 'Primitive Negro Sculpture' and he began to appreciate that there were other people who did have respect for African Art and its own qualities.

He began to sculpt in an interpretive rather than representational way.

The final straw came for him when he was offered a position in his local government as a carver of tourist souvenirs. His contribution on a spiritual and artistic level was being denied and the crisis he was suffering became untenable.

When he left South Africa for Paris in 1938 he turned to painting using colour washes and some oils. While adopting modern methods he constructed ancestral figures into his increasingly abstracted paintings with seemingly spontaneous bursts of colour and impulsive brushstrokes.

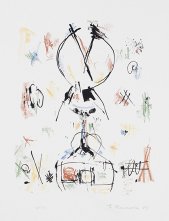

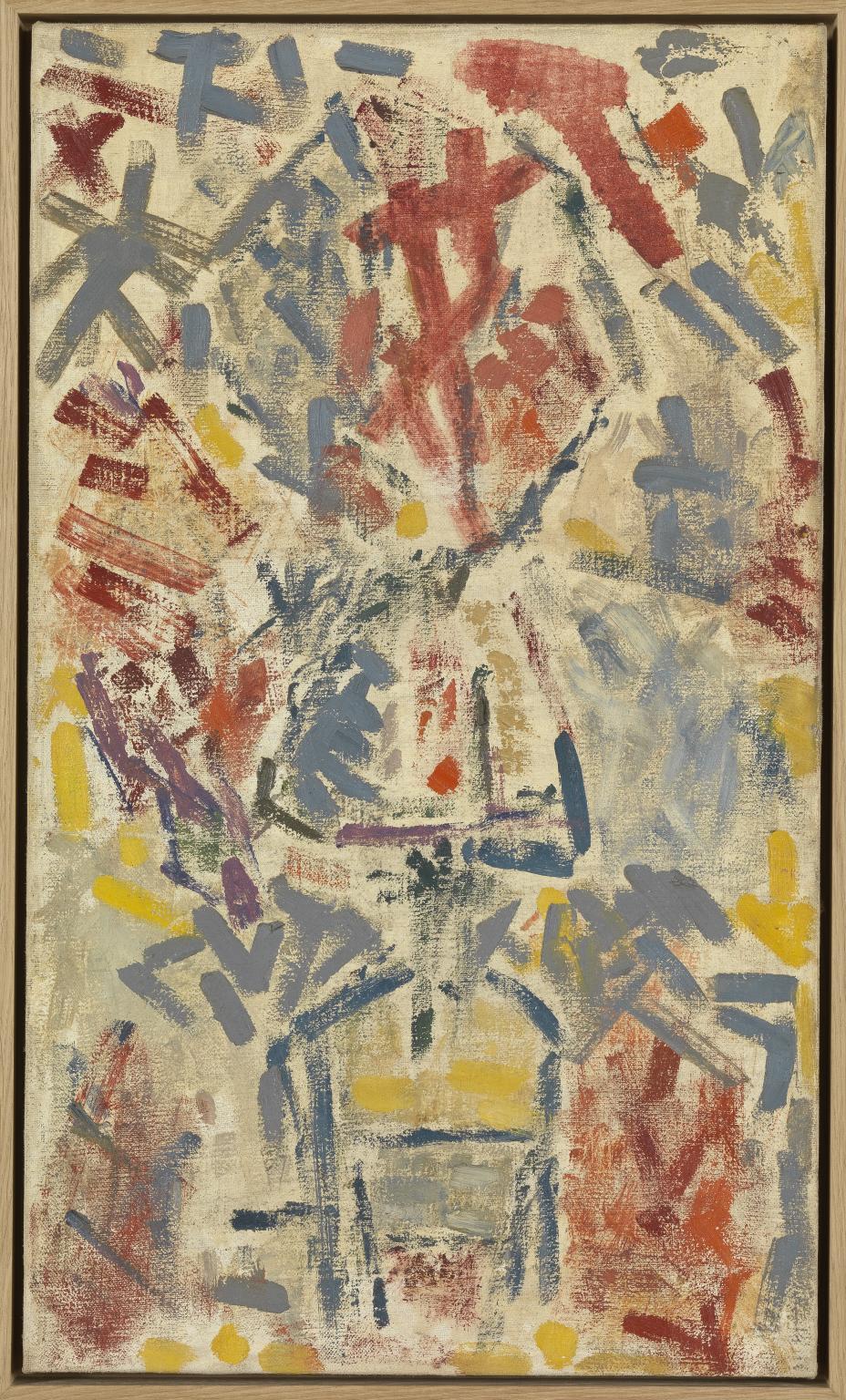

Lithograph, untitled

Lithograph, untitledBesides being at the forefront of the emerging African modernists he was one of the leading intellectuals of his time and he sought to engage with the dialogue that was happening in Europe and America over African art forms and the impact they were having on the avant-garde. His own philosophy was that the individual finds himself in the collective; he had a holistic approach to his art and recognized he could have a healing role to play.

While adopting modern methods he constructed ancestral figures into his increasingly abstracted paintings.

In 1990 he developed a very personal language; a calligraphy of script-like characters rendered in ink and pastel drawings that simultaneously mask and reveal ancestral figures.

Mancoba died in Paris in 2002 having been recognized as a pioneering African modernist with two honorary doctorates in his home country.

Ben Enwonwu

Ben Enwonwu was born in 1917 in Onitsha, Eastern Nigeria. He was exposed to art at a very early stage as his father was a sculptor in the traditional Igbo style. His 5 decade long career in painting and sculpture was an extraordinary achievement and his work continues to inspire and be admired the world over.

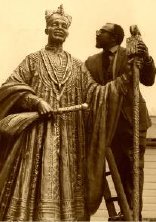

Ben Enwonwu, sculpture of Sir Ladipo Ademola, 1968.

Ben Enwonwu, sculpture of Sir Ladipo Ademola, 1968.In 1950 he said a very true thing: "Art is not static, like culture. African art has always, even long before western influence, continued to evolve through change and adaptation to new circumstances"

Ben Enwonwu is seen here with his sculpture of Sir Ladipo Ademola, The Alake of Egbaland in 1968.

This piece was presented to the United Nations some 10 years later as a symbol of peace and the emergence of an independent African nation. It very finely and successfully integrates Edo-Igbo heritage and modern modes of representational figures and has molded itself into the national consciousness of most Nigerians.

Ben's work indeed altered as he met with different influences and as his country moved through dramatic changes. In 1955 he created a sculpture he called 'Anyanwu' or the Awakening.

Enwonwu's works such as the series 'Negritude', have achieved some of the highest prices existing on the world art market for African modernists.

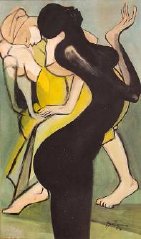

Negritude I

Negritude IFor a child who started off drawing in the sand with broomsticks, he has had an impressive career spanning at least 50 years, accomplishing mastery in several disciplines of sculpture; wood, bronze and cement, and in painting and drawing.

He is most well known for his sculpture of both strong African and Western imagery as well as his paintings of masks, dances and masquerades. These paintings are a contrast to his often smooth minimalist ebony sculptures and their wild dancing postures and elongated figures vibrate with energy.

It was his experimentation with combining Nigerian traditional art forms with modern trends of formal strength of execution that inspired the government to promote art in Nigeria as a worthy academic pursuit and encourage national unity and pride.

Ibrahim El Salahi

The third of this trio of African modernists, this artist was born in Omdurman, Sudan in 1930.

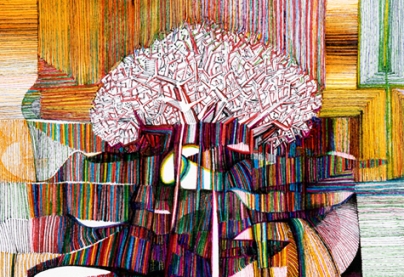

'Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams', 1961-65, enamel and oil on cotton

'Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams', 1961-65, enamel and oil on cottonEl Salahi has lived a lot of his life in and out of Sudan due to a desire to further his education, political pressures in the midterm of his years that forced him into self-imposed exile and cultural diplomatic duties later on that saw him live part time in Oxford. This has allowed his work and his voice to be seen and heard in many institutions and galleries around the world.

Ibrahim El Salahi, The Tomb

Ibrahim El Salahi, The TombHe lead an art school known as the 'Khartoum School' in the 1960's which came to be recognised as an emerging African modernist and pan-African movement.

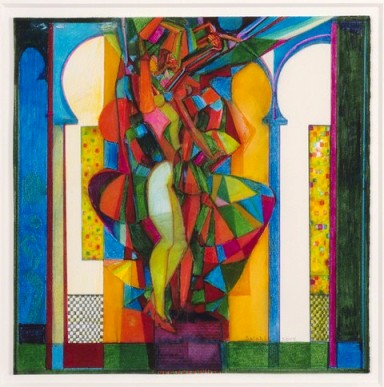

His own work moved from muted earth tones and linear compositional styles to more vibrant colour and abstracted human/animal figures in geometric designs by the late 1970's.

El Salahi, The Tree

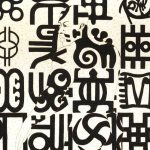

El Salahi, The TreeFinally in his latter period he worked in black and white almost exclusively.

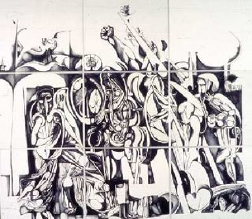

In 1975 while working as Cultural Minister he was imprisoned for 6 months without trial, accused of anti-government soliciting. While incarcerated in the notorious Kober prison in Khartoum, he spent his exercise time drawing in the dirt; mind scribbles that had to be rubbed out every day but were revived in his most famous art work, 'The Inevitable' which he created in 1984-85.

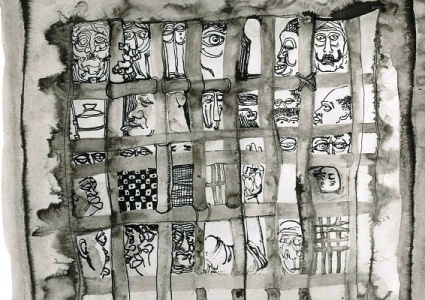

Ibrahim El Salahi, Untitled drawing, 1963

Ibrahim El Salahi, Untitled drawing, 1963Harmon Collection

It consists of 9 panels, challenging the notion of war and genocide yet it was created as a celebration in recognition of the determination and courage of all those who suffered during Sudan's civil wars and brutal dictatorships. Currently it is housed in the USA at the Herbert F Johnson Museum of Art, NY waiting until the day when civil rights are restored and it can be returned to the Sudan.

The Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA) recently acquired El-Salahi's Prison Diaries; a 37-part series that recall and document his time spent in prison. He produced these drawings while he was under house arrest and they are one of his most prized possessions.

They bare testimony to the many aspects of living in confinement... the subject matter covers everything to do with daily life both inside and outside the cell and contain many intimate impressions.

Jimo Bola Akolo

Jimo Bola Akolo was born in Kogi State, Nigeria in 1934, the grandson of a master basket weaver. Design was in his genes.

Akolo is best known for his impact on the formation of the Zaria Art Society in 1958. This group denounced Western art influence and encouraged traditional, cultural styles of art and creative expression at the College of Arts, Sciences and Technology in Zaira, Nigeria.

Jimo Bola Akolo, 'Taking a Break', 2003

Jimo Bola Akolo, 'Taking a Break', 2003By 1960, Nigeria's year of independence, he had broken away from this group delving deeply into his own country's traditions and folklore and drawing inspiration from them to create a new visual vocabulary. His paintings reference designs and patterns from Hausa architecture, incorporating bold colours, geometric forms and loose brushstrokes.

Jimo Bola Akolo, 'Infantry', 1965

Jimo Bola Akolo, 'Infantry', 1965He left Nigeria to study abroad in the UK and then Indiana, USA. He achieved many accolades during his long career as painter and as a pioneering educationalist and administrator. He exhibited broadly in places like São Paulo, Brazil, London, Havana Cuba and participated broadly in exhibitions in his home country.

His work is justly receiving the attention it deserves as can be seen by his inclusion at the Frieze Masters in London, 2024. Represented by Ko Gallery the presentation includes oil paintings and drawings spanning 1960-1990's.

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.