Search this site ...

African Textiles

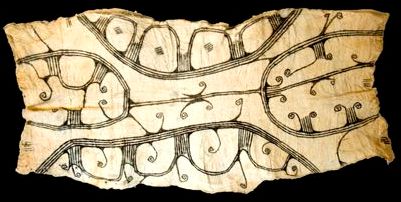

Skirt (Ntshak), Kuba Cloth, Zaire, 20th C, Textile Museum

Skirt (Ntshak), Kuba Cloth, Zaire, 20th C, Textile MuseumAfrican textiles are the major form of expression that Africans use to define themselves.

They have used cloth not only for personal adornment but also as a powerful medium of communication for many centuries. Their importance has often been overshadowed by traditional sculpture and masks but in this day and age, we see how African textiles have become the most significant medium by which contemporary African artists are illuminating the connections and continuities between past and recent modes of African artistic expression.

African textiles are also a means for us to acquire insight into the social, religious, political and economic complexities of many African communities whose sophisticated cultures we may otherwise remain ignorant about.

Besides that, African textiles are just so glorious to behold!

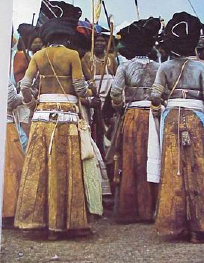

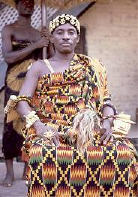

They speak to me of ancient kingdoms and civilizations where a man was revered and respected, judged by the voluminous splendour of his cloth. Kente fabric woven in strips in silk for the Asante Empire and its’ Royal Court; skirts woven from raffia wrapped around Kuba King’s resplendent menservants and indigo blue tunics that are embroidered with elaborate design and intricate pattern by the Fulani tribe who live in the Niger delta and add a dignitary air to the wearer.

Very few ancient textiles have survived the adverse climactic conditions of Africa.

Although numerous linen fragments have been collected from Egypt pre-Christ, the picture for sub-Saharan Africa is less apparent and the earliest textile found in Niger dates to the second half of the 8th C AD.

Following this, the Igbo Ukwu cloth fragments have been dated to the 9th C and in the 11th C AD pieces found in burial caves in the Tellem cliffs in Mali have been attributed to the ancestors of the Dogon. Single-heddled vertical and horizontal ground looms were observed in production by the Portuguese when they arrived in Africa in the 15th C and Kuba cloths were discovered in Zaire in the 16th C.

Uses of African textiles

- African textiles have had and still have an exceptional significance as a means of communication, information and mutual association within particular communities. There is spiritual and historical significance in not only the choice of colours, dyes and type of threads used, but also in the decorative element, the symbols used and the figural compositions which are directly related to historical proverbs and events. They represent a form of story telling often taking the place of the written word and convey messages of importance for an individual, family, or larger social unit.

- African textiles are often used for social and political comment, for commemorative purposes marking special occasions like political or tribal events, weddings, funerals, burials, naming ceremonies. Historically, their usage was controlled by chiefs and regional leaders and they were distributed with favour.

- As personal adornment they are wrapped as skirts round waists and hips and thrown over the shoulder or made into tunics and robes. African textiles are not always worn but sometimes used as backdrops against which public ceremonies were held.

- African textiles are also used quite simply as items of warmth or cover but centuries of tradition and a culture of crafting beautiful items imbues some African communities with an air of elegance and vibrancy in their clothing attire that one does not experience in the Western world which chooses conformity above individual expression.

Methods of producing African textiles

Mbuti cloth

Mbuti clothCloth production methods include woven, dyed, appliquéd, embroidered and printed techniques. Printing and dying and hand painting occurred on all types of woven cloth and also on leather (hide) and bark.

Fibres traditionally used for weaving are predominantly cotton but also include wool, silk, raffia, bark and bast fibres like flax and jute which produce linen cloth.

It is very seldom that a textile piece is produced by just one process and when one considers that everything is hand executed in mostly rural circumstances, one has to admire the commitment and skill involved in making the piece. African textiles are highly collectable artworks and will continue to gain in value as traditions disappear and the authentic items become unavailable.

Raffia fibres

Raffia fibresTribal textile art

The following have been identified as some of the more well-known tribal African textiles and they can be studied in further detail on separate pages.

- Adire, indigo cloth from the Yoruba of SW Nigeria

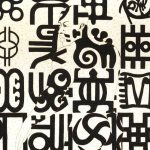

- Andinkra, stamp printed cloth from the Asante of Ghana

- Asafo, appliqued flags from the Fante of Ghana

- Aso-Oke, woven strip cloth from the Yoruba of Nigeria

- Bark cloth, painted from the Buganda of Uganda

- Bogolan, mud cloth from the Bamana (Mande) of Mali

- Dida, raffia cloth from the Dida of the Ivory Coast

- Fila, dye-painted cloth from the Senufo of the Ivory Coast

- Kaasa, woollen blanket from the Fulani of Niger Delta, Mali

- Kente, woven appliqued cloth from the Asante and Ewe of Ghana

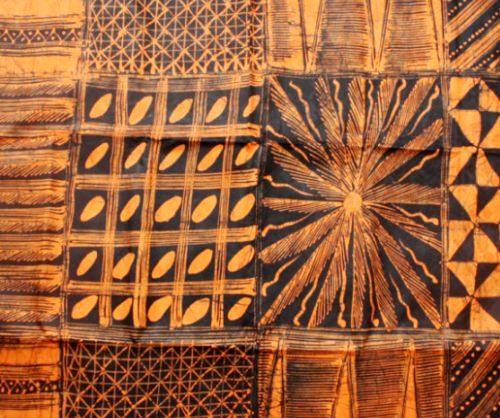

- Kuba, Shoowa cloth from the Kuba of the DRC, (Zaire)

- Ndop, resist dyed indigo cloth from the Bamileke of Cameroon

Textile Tunic(Bororo) 20th C Metropolitan museum, African textiles

Textile Tunic(Bororo) 20th C Metropolitan museum, African textilesTraditional clothing

African clothing can be a symbol of status, creativity and allegiance to tribal roots.

Traditionally, there are men's robes; some produced as symbols of prestige or even protection in battle, women's robes; wrap around cloths worn as skirts by men and women; body wrap blankets acting as coats or ceremonial tokens; loin cloths, aprons and any manner of headdress and adornment.

A few examples...

- Agbada, robe of the Yoruba tribe of Nigeria

- Bororo, tunic of the Fulani in Niger

- Mabu, feathered Cape from the Bamileke of Cameroon

- Ibhayi blanket body wrap from the Mfengu of South Africa

Thembu women dress, South Africa, Ezakwantu

Thembu women dress, South Africa, EzakwantuModern African textiles

Today, in Africa, printing, weaving and dyeing textiles remains a craft that provides both income and creativity for many artisans across the continent.

There are a myriad designers, workshops and co-operatives who produce either handmade fabrics or minimum order lengths for special projects or retail/gift shops. Smaller scale semi-industrial enterprises can run lengths of anything from 200-1000 m lengths to special order.

The product can be used for retail sales or developed further into fashion garments, furnishing textiles or home décor items.

Urbanstax has a collection of modern adire fabric which is hand-drawn and hand-dyed in Nigeria. Since each fabric can be made of any mix of symbols that tell a story, these cloths can be seen as an art piece, unique and individualistic and contemporary in their hues.

When a designer collaborates with a skilled craftsperson then all sorts of amazing ventures are realized.

Below are just a select few who are absolutely making a difference... not just to textile design but also to community's welfare as well as keeping alive the skills of countless years of tradition thus ensuring continuity of a valuable African cultural and economic asset.

Weave

Aissa Dione, Senegal - ADT

Born in Senegal, lives in Dakar. Aissa Done works with interior and fashion designers all over the world who recognize how successfully she incorporates ancestral Mandjaque techniques with innovative and original interpretations of this craft.. creating truly modern woven fabrics for furnishings, furniture and fashion.

Aissa Dione

Aissa Dione Aissa Dione

Aissa Dione Aissa Dione, Dak'Art 18

Aissa Dione, Dak'Art 18In 1993, she formed her company named ADT (Aissa Dione Tissus) starting with just 3 master weavers. Incurring many challenges along the way she has survived to employ over 100 weavers who work with modified looms which can weave wide-width fabrics for the furnishing and upholstery business.

Having had to import cotton yarn from Turkey and Egypt through the last decade she actively engaged with the Senegalese government, encouraging them to revive the cotton industry, both growing and spinning. Technical schools are also being established to support the industry.

She has borrowed her geometrical patterns from various sources including the Kuba, Zaire and Mandjaque designs from Casamance, Guinea Bissau and Gambia.

Her sophisticated collections are made more contemporary by graphic repetition, bright hues and mixed yarns. In her fabric make-up she mixes cotton with raffia or silk and also uses plastics to produce strong fabrics for upholstery. Her overall aim is to revive traditional African woven textiles and assure their future while making sure industry survives.

Atmek and Eco yarns, Ghana

This is a very modern co-operative, the merger of master Kente weavers and the suppliers of Tencel yarn to Ghana.

The fabrics are upholstery weight, a combination of silk, tencel and cotton.

Hana Getachew, Ethiopia - Bole Road Textiles

Bole Road, Wollo gabi blanket

Bole Road, Wollo gabi blanketHaving left Ethiopia at 3 years old, Hana Getachew returned as a young adult.

Feeling intensely inspired and connected to her heritage she set up Bole Road Textiles with the commercial/design side operating in Brooklyn NY and the artisan/production counterpart set up in Ethiopia.

Bole Road, Heritage collection

Bole Road, Heritage collection Bole Road Textiles Konso Inspiration

Bole Road Textiles Konso InspirationDesigns and concepts based round the wealth of natural beauty and culture existing in Ethiopia are formulated by Hana and then digitally sent to Ethiopia for weaving into fabric.

Traditional motifs are used, re-coloured and re-spaced... successfully re-invented in a modern interpretation for today's contemporary market.

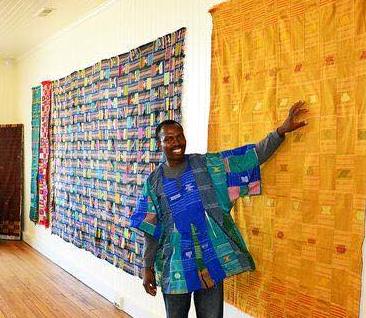

Gilbert 'Bobbo' Ahiagble, 1944-2012, Ghana

A ewe artist and master weaver, 'Bobbo' Ahiagble' perfected the craft of weaving Kente cloth while at the same time developing CIKW (Craft Institute of Kente Weaving).

Master weaver, 'Bobbo' Ahiagble

Master weaver, 'Bobbo' AhiagbleSince 1975 he has combined developing his own art with weaving demonstrations outside Ghana, travelling abroad and passionately promoting his craft. His masterful wrappers are contained in many collections over the world including the Smithsonian in Washington.

'Bobbo' Ahiagble, kente cloth

'Bobbo' Ahiagble, kente clothOver time he has developed unique skills and designs that have created his signature style of weaving-subtle combinations of weft hues with multicoloured warps.

He has also used secular motifs as well as traditional ones.

Chapuchi' Bobbo' Ahiagble

Chapuchi 'Bobbo' Ahiagble is one of the sons of Gilbert 'Bobbo' Ahiagble.

An artist in his own right he continues the heritage of his father, keeping the skills of weaving kente and ewe cloths alive and intact. He also lectures abroad and demonstrates at home in Aflao, Ghana where he endeavors to keep the legend of these beautiful cloths relevant to modern day Africa.

Chapuchi 'Bobbo' Ahiagble

Chapuchi 'Bobbo' AhiagbleFor viewing Chapuchi 'Bobbo ' Ahiagble at the Smithsonian watch this video link

Tesss Atelier, Senegal

Formed by Mai Diop (aka Veronique Picart ) in 2001 together with Assane Diop who started a weaving workshop close by the studio. Together they have built this up as a business that remains small but true to its original inspiration.. committed to the preservation of keeping Manjak loincloth production alive in the modern era.

Without the beliefs attached to it and a desire by local communities to keep the traditions associated to its manufacture alive, this rich heritage of symbolism and historic significance would fall away.

Bedspreads, tablecloths and special orders from this atelier have found their way into homes all over the world. Modern interpretations like this one below show traditional design motifs on a white ground.

Keeping it visual, fresh and illuminating is what Tesss does so well.

Dyeing

Boubacar Doumbia, Mali - Ndomo

Part of the revolutionary Groupe Bogolan Kasobane, an artist's collective formed in the 1970's who researched and explored the predominantly female art of fabric dyeing and weaving, founding member Boubacar Doumbia has become, today, a leading proponent of contemporary bogolan production in West Africa.

Taking it back to its roots and honoring the craft of dyeing with natural plant-based dyes and hand-painted designs covered with mud straight from the Niger River, he has recently worked in collaboration with Habitat UK to create a fabulously graphic and urban-based motif range of textiles to be used in furnishing products.

Boubacar/Habitat collaboration

Boubacar/Habitat collaboration bedspread Habitat

bedspread HabitatFurther to that and more far-reaching, Doumbia has developed a social enterprise in the village of Segou called Ndomo.

Here in this architecturally distinct environment he has set up a 10 year program for young males to learn and practice not only the technical skills to carry on the traditions of bogolan dyeing and printing but also the entrepreneurial skills to create businesses of their own.

Smaller widths of fabric are handwoven on site while wider cloths are developed on looms. The dyes used are earth, vegetables and indigo. The cotton is locally grown and the mud from the Niger has all the iron required in it to turn the dye black (3 coats for black and 2 for grey).

Ndomo is an example of a sustainable industry coupled with eye-catching, contemporary design.

Aissata Namoko, Bamako – Djiguiyaso Co-Operative

Aissata Namako heads up Djiguiyaso Co-operative in Bamako, Mali.

This enterprise provides work for more than 100 women. Based on bogolan indigo tie-dyeing, the women's skills in crochet, weaving, spinning, cutting and sewing are further developed.

Aissata Namoko with Djiguiyaso cloths

Aissata Namoko with Djiguiyaso cloths

Djiguiyaso at Africa Now NY

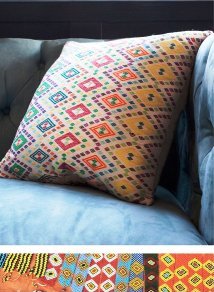

Djiguiyaso at Africa Now NYPrimarily 100% cotton, the atelier makes up cushion covers, bedspreads, bags, scarves, clothing etc using the traditional methods of dyeing but injecting new designs and motifs for a more contemporary look.

Kofar Mata Dye Pit

The Kofar Mata dye pit has existed in Nigeria since 1498 and still operates although only just over half of the 100-so pits are currently used. Pits are passed down from generation to generation and tightly managed... while the expertise and secrets of indigo dyeing of African textiles are closely guarded.

In general fabrics are dyed in holes below the ground in solutions made from mixtures of water, ash and dried indigo twigs. Frequent dips of the cloth are required for particular depths of colour to be achieved.

Nike Davies Okundaye, Nigeria

Chief Nike Davies Okundaye

Chief Nike Davies OkundayeChief Nike Davies-Okundaye was born in Kogi state, Nigeria in 1951 to a cultured family of musicians and skilled artisans. Her grandmother was particularly influential in nurturing Nike's interest in textiles and the art of dyeing, printing and weaving, specifically indigo and adire.

She spent a lot of her life in Osogbo, a major centre for art and culture where she embraced everything to do with Nigerian culture. She has formed 4 art centres and a large gallery. Now days, she lectures and speaks around the world and is as global a figure as they come, accepting and receiving many awards for her contribution to the arts.

She loves to wear her textile art and cuts a dramatic and colourful figure with noticeable headdresses and jewelry adornment.

Her own work is semi-abstract and semi-representational - full of underlying line drawing defining figures and compositions by areas of repetitive pattern, colour and geometric shapes.

Here in the image above, Okundaye works hand in hand with Tola Ojuolope and Distill2710 on a project for the communal lounge of 1:54 Contemporary Art Fair, London... a beautiful array of Adire hanging cloths... Nigerian batik and Indigo dyed textiles representing the textile traditions of West Africa but re-interpreted in a contemporary manner by this pioneer artist.

Contemporary textile designers

The following designers are committed to their disciplines, but as designer-artists they also choose to express themselves in a very personal way with one-off pieces that push boundaries outside their fields of expertise.

Johanna Bramble

Multi-skilled, versed in weaving (manjak, ikat), fashion accessories, monumental works/tapestries, embossing techniques, lighting and furnishing fabrics Johanna Bramble is devoted to her craft.

Johanna Bramble - dak'art 18, CAA photo

Johanna Bramble - dak'art 18, CAA photoBorn in 1976 in France and having studied design and applied arts in Paris, she settled in Dakar in 2008 after having met the Senegalese designer Ousmane Mbaye. A workshop was started with 4 Senegalese weavers but more recently she has engaged them in producing fabrics for the future, using not only cotton but also mixes with non-traditional fibres such as metallic yarns, viscose, copper, silk and even paper.

In an interview with IAM magazine issue #2016 she explains her philosophy on weaving saying it has a language of its own and can be an extension of one's soul. She sees Senagalese fabric as being full of meaning and she tries to impart this deeper connection to her own ranges by way of colour, symbols and feeling. Rhythm exists in not only the act of weaving (the motion between the weaver and his assistant) but also in the pattern, the design and the arrangement of colours.

Her colours can be either sombre and neutral or go quite the other way being injected with joyous, vibrant hues. The technicality of her work is unquestionably sophisticated being thoroughly researched, tried and tested. The speciality comes from the new interpretation of traditional geometrics and contemporary more secular/urban motifs.

She has exhibited her own personal development work in 2 Dak'Art Biennale shows.. 2016 exhibition "Flamboyant" and "Aborescence" in 2018.

Mai Diop

'Evasion' kuba inspired cloth - Mai Diop

'Evasion' kuba inspired cloth - Mai DiopMai Diop, the force behind Gallerie Tesss Atelier in Senegal is also motivated to be an originator and produce her own, personal, contemporary works which are dense in expression and execution. Woven strips of canvas are hand-dyed in baths of natural dyes. More muted in colour than her commercial cloths, they pay homage to many influences.. like kuba cloth or paving stones, flowers or stained glass; she takes inspiration anything around her.

Her signature treatment is to print soft wax over them creating a stiff wall-hanging that crackles and whose textures can be seen if held up to the light.

Aboubakar Fofana

Aboubakar Fofana was born in Mali, raised in France and spent time in Japan. A multi-disciplinary artist and designer, he has found art in the tradition of indigo dyeing. His working mediums include calligraphy, textiles and natural dyes.

Aboubakar Fofana, cloth installation

Aboubakar Fofana, cloth installationHis contemporary work is original and inventive, adapting his learned techniques from Mali and Japan onto abstract canvases and using strip weaving to create sculptures and installation pieces.

While greatly absorbed with re-inventing and re-defining West African textiles into glamorous textiles and exciting installation projects, he also has his feet planted firmly in the soil in Mali.

Here he is involved with creating a farm community in the district of Siby where he hopes to successfully farm the 2 types of indigo that exist in West Africa and rebirth fermented indigo dyeing. His permaculture model includes a model based around local food and medicine as well as indigo and cotton plants.

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.