Search this site ...

Art workshops SA

Polly St & Rorke's Drift

In 1944, John Koenakeefe Mohl's "White Studio" in Sophia town, Johannesburg laid the foundation for the establishment of fine art by black artists in South Africa.

In 1952, the artist Cecil Skotnes was appointed by the Johannesburg City Council as Cultural Recreational Officer for the Polly Street Recreational Centre. Under his guidance and vision, it was to become a thriving hub of creativity and a significant training ground for a whole generation of artists.

Polly St Art Centre

Polly Street Art Centre held fairly informal classes for black students often mentoring them with established white artists so that a dialogue began to take place and shared exhibitions were held. Skotnes was cautious of destroying their 'Africanism' with Eurocentric teachings but still, recognised art teaching was practised with life-drawing, still-life, landscape and abstracts all being encountered by the students.

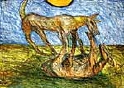

Lucas Sithole

Lucas Sithole1931-1995, 'Begrip'

They were, however, encouraged to create at home and to establish themselves in the marketplace as quickly as possible in a bid to make them self-supporting. Watercolour was a common choice due to costs and availability of materials and terracotta became the medium used in sculpture. The art produced there followed two avenues: a township style and a neo-African style which was influenced by traditional African sculpture.

The emergence in the late 50's and 1960 of artists such as Sydney Kumalo, Lucky Sibiya, Ephraim Ngatane, Lucas Sithole, Louis Maqhubela, Durant Sihlali, Ezrom Legae and David Mogano identified modernist black art in South Africa. Their distinctive work spoke of an individuality and a recognizable visual African expression. Sydney Kumalo's work especially shows how exploratory the artists of the Centre were in finding a new language that was informed by Africa. He was influenced by African sculpture which had been introduced to them by Skotnes via Egon Guenther.

It must be remembered that at this time there was very little exposure to the traditional art forms being created by African tribal artists. Skotnes was so moved he gave up painting and turned to relief carving and print making and the sculptors in the group like Kumalo and Leonard Matsoso abandoned figurative work, embracing more expressive and modern forms.

Polly Street Art Centre was replaced by the Jubilee Centre during which time Ezrom Legae was notably first a student and then a teacher but that too closed its doors which ostensibly removed a meeting place for artists in the Johannesburg area.

Ephraim Ngatane, 1938-1971

Ephraim Ngatane is commonly referred to as the 'Hogarth of Soweto' for his acutely observed images of SA township life. Somehow he managed never to glamorize the degradation of being poor but treated it as he saw it, with directness and empathy, capturing the warmth that still existed, the music, sport and social life and painting it with vibrancy and colour.

'Township builders', 1969

'Township builders', 1969Skotnes said of him, 'We soon discovered that painting was not a hobby for him but a way of life.' He was hugely prolific in his short life, a recent retrospective at the Standard Bank Gallery in Johannesburg showed 80 pieces of work produced in less than 2 decades. His true legacy will be the ability of us to comprehend, through viewing his work, the absorption of modernism in SA and how it shifted to abstraction.

His paint application alone strongly exhibits this.

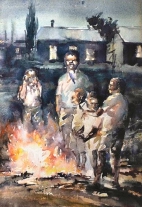

'Figures around Fire'

'Figures around Fire'Durant Sihlali, 1935-2004 was also concerned with recording the harsh life of the townships but it was softened by his exquisite and highly skilled use of watercolour, the medium he perfected. His work bore witness to the imposition and reality of separatist living and he was moved to document, not just for himself, but also for Africa a moment in time and a way of living.

In his later years he continued to be hugely inventive and his art called into question the importance of honouring sacred rituals in modern Africa.

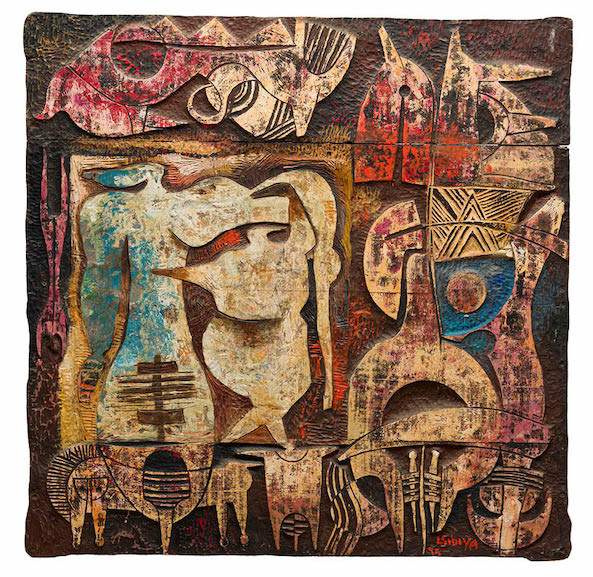

Louis Maqhubela won the Adler Fielding prize for 'Artists of Fame and Promise' in 1966 out of a field of 900 entries. This enabled him to travel abroad where he came into contact with Douglas Portway who greatly impressed and influenced him.

Initially concerned with township subject matter, he evolved to more abstract modes of painting and began to use oils, often executed on paper and featuring small abstract linear configurations using dark tones and flashes of colour.

Today he has a specific language of forms which are the basis of his particular narrative.

Rorke's Drift Art and Craft Centre

Rorke's Drift Art and Craft Centre was founded in Zululand in 1962 as Polly Street came to an end. This centre was to have a considerable impact on art and craft in South Africa , intensely so for the next two decades but lasting even to this day where it still exists in a different format (Katlehong Art Centre) in the heart of the Kwa-Zulu Natal countryside.

Started by a Swedish couple, Peder and Ulla Gowenhuis with the primary function of advancing South African art, an initiative taken by church authorities in Sweden, it melded European, American and South African teaching influences with deep rural and traditional values to produce unique forms of art with emphasis on skilled, technical fine art like printmaking as well as textiles and pottery.

There were two sections to the Centre, the Fine Art division and the Arts and Craft section but there was a lot of crossover between the two causing a significant elevation of personal expression in the crafts. This was an important occurrence and meant that greater value was attached to the product and sales were good both locally and overseas.

The other interesting fact is that it started out primarily with women being involved (Mbatha was the only male at its conception) and as men started to be drawn in, the sexes kept their areas of expertise mostly separate; women in pottery, tapestry and textiles and men in printmaking. There were exceptions with some of the men creating designs for the tapestries and women who took pottery into a sculptural sphere.

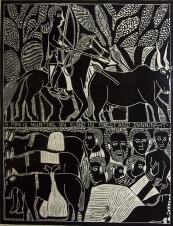

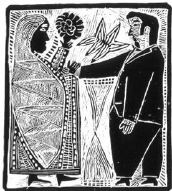

'A man is hunting an eland in the forest and skinning it', 1979

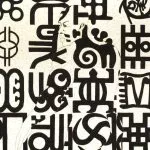

'A man is hunting an eland in the forest and skinning it', 1979John Muafangejo, Azaria Mbatha, Cyprian Shilakoe and Vuminkosi Zulu were just four male artists who developed as printmakers at the Centre during the sixties. Gowenhuis was adamant that work produced here should be useful and this form of fine art lent itself to the commercial world.

However these artists transcended these boundaries and established a recognized style that stood on its own as fine art even to this day.

John Muafangejo had a looser style than Mbatha and was less concerned with religious subject matter being more engaged with his environment, depicting rural culture and using African imagery.

Dan Rakgoathe attended Rorke's Drift from 1967-69 and was very friendly with the young Cyprian who tragically died at 26 years old. Together they produced work rich in symbolism being concerned with philosophical, spiritual and mystical aspects of the human condition in society. Isolation and separation were both notions that they personally experienced or were drawn to depict.

Rakgoathe was a master exponent of linocuts, working mostly in black and white until 1970 when he started to work in colour, while Shilakoe used etching and aquatint to give his work a haunting effect.

The Fine Art section of the Centre closed in 1982 which was seen as a great loss but there appeared to be a tension existing between students of rural and urban areas. The urban students who were primarily in fine art were involved with the growing demonstration against apartheid. It is interesting to note that from then on the potential growth for creativity at the Centre declined and a particular style set in.

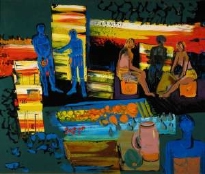

'Street market', Walter Batiss

'Street market', Walter BatissThe 60's and 70's provided a period for exceptional design and art to be created under a unique set of influencing factors.

It must be mentioned that Walter Batiss, one of SA's foremost artists and educationalists, a great innovator who sought liberation of the mind, had an association with Rorke's Drift Art Centre in the 70's. The connection was unquestionably positive and uplifting on both sides.

It must also be noted that this was a crucial period for white artists in South Africa who sort to establish their own credibility in the face of Eurocentric gallery owners who often featured international artists with a smattering of locals included.

There were exceptions... Henry Lidchi Gallery showed Robert Hodgins and Zimbabwean sculpture which was making its mark with a wave of First Generation Sculptors under the direction of Frank McEwan and the Goodman Gallery was quick to see the growing potential of existing dynamic SA artists. Madame Haengi of Gallery 101 also promoted the more non-conforming artists of the era.

White Art selling in more commercial galleries was intent on promoting the myth of the 'Garden of Eden' that South Africa (and Africa) was meant to be. Romantic landscapes, wildlife and native studies sustained the fantasy so those white artists who sought to portray the realities of their existence didn't have it easy. Granted, they were mostly better off and not restricted by freedom of choice in where they traveled or the materials they used.

They could also succumb to the pressures of international modernity and there was a lack of confidence factor and identity crisis that existed round SA artists well into the 21st Century.

The Development of the Black Consciousness movement

Black artists created under hugely difficult and compromising conditions and had very little outlet for their work especially if it had political overtones which increasingly, it did. Artists were often detained or imprisoned as a result of their political activity or some left the country to study or work abroad.

Several talented young artists dies in tragic circumstances, often violently as a product of the harsh society in which they survived including Ephraim Ngatane and Julian Motau, (1948-1968), a brilliant young draughtsman who had a solo exhibition at the newly opened Goodman Gallery in 1967 showing a proliferation of gut wrenching visual imagery (charcoal drawings) of the turmoil he encountered and deeply felt in his world.

He died a year later in a random killing in Alexandra Township just 20 years old.

The artists Dumile Feni, the 'Goya' of the townships and the photographer, Ernest Cole, turned to producing art that reflected the social reality of their repressed world in turbulent imagery.

Both of them chose self imposed exile so they could continue their work abroad without fear of retaliation and the freedom to create without censorship. It was also an economic decision as both struggled to live off their art, encumbered by the colour of their skin and the ability to move around freely given the restrictions of the Pass laws. (One had to prove full-time employment to live in urban areas). Feni also broke the colour bar by having an affair with a white woman which was a legal offence under the Immorality Act in South Africa.

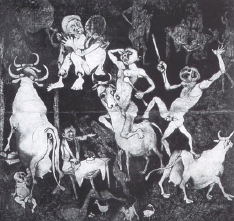

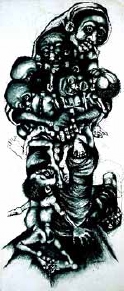

Dumile Feni, 1942-1991 African Guernica

Dumile Feni, 1942-1991 African GuernicaDumile Feni left SA in 1968, went to live in London and enjoyed considerable success with his art. He then went to live in the States in 1979 where he remained until his death in 1991 in New York. He was chiefly a draughtsman but also sculpted and had a great love of jazz so sometimes his work celebrates music.

His work can be sensual, using bulls and horses as sexual metaphors, or full of pathos depicting compassion and tenderness and dignity to those who suffer. Figures are central to his work and he uses distortion to express emotion and reinforce the visual sensation. To some extent his work belongs to the realm of the fantastic.

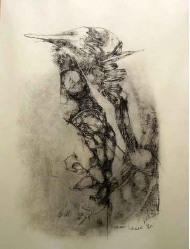

Ezrom Legae was born in 1938 and died in 1999 just a year after he acquired a new studio at the Bag Factory, Fordsburg, having spent his whole life committed to producing brilliantly sensitive yet compelling work that shocked and deeply moved the viewer at the same time.

Legae's work is frequently a political statement of both power and compassion; even his sculptures of burnt flesh, necklaced people or dying beasts depicting human agony have a lyrical content that rescues the viewer from submersion into their own horror. A master draughtsman, he is also recognized for his sculpture in clay and bronze and after 1970 he worked predominantly in this medium, creating figures, heads and animals and sometimes using both human and animal form together to create powerful allegorical visuals.

'The Rider'

'The Rider'Such are the drawings entitled 'Freedom is Dead' which were exhibited in Chile in 1982; so blatantly anti-apartheid and anti-State was the content that it could not be shown at home.

It took great courage to portray the truth of what was happening at home just as it took great sensitivity to undertake a tribute to Steve Biko after his death which he did in 1979 in a series called 'Chicken' which despite its delicate drawing nonetheless had immense impact.

His identification is always with the human condition and his own spirit.

Artists like Fikele Magadledla created another development of a more aspiring nature dwelling on the portrayal of beauty and hope, mystery and poetry in an effort to have black art depicted as something other than tragic and to elevate black people's own self identity. Mysticism links him squarely to his African experience.

It became very important that art took on a new reality, a self determined one. Black Consciousness sought to achieve just that.

In 1982 and 1985, two organizations evolved, the former being the Triangle Arts Trust, promoting networking of artists and workshops led by artists, and the second was the formation of Thupelo which has now been an informal feature of the art scene in SA for 25 years.

Both encouraged fresh thinking, exchange of ideas, experimentation and professional development with an emphasis on process during workshops rather than resolution of work.

David Koloane, 1938 - 2019

Central to Thupelo was David Koloane, a co-ordinator and not only a key figure in the associated programmes but a practicing artist who was committed to involvement on a broad scale, opening the first black Art Gallery in Johannesburg in Market Precinct in the late 70's.

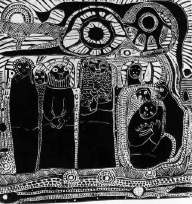

David Koloane

David Koloane

He went on to co-ordinate the visual arts of the Culture and Resistance Festival held in Botswana in 1982 and in 1995, curated the well honed exhibition 'Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa' at the Whitechapel Gallery in London. He wrote in the accompanying catalogue "The pervasive role played by politics in the existence of the South African populace affects both victims and perpetrators alike, and therefore every sphere of life."

His work has the same abstract intent that is reminiscent of Jean Michel Basquiat.

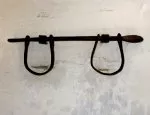

Koloane hovers on the interface of international modernism and commercial South African township art. He uses assemblage as a medium with random process and his drawings possess the same haphazardness of technique but energy of interpretation.

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.